SEOUL—Jeong Bo-ram’s new fascination has him chasing mass-produced pastries, delivery trucks—and his childhood memories.His targets are $1.20 bakery items sold with random Pokémon stickers that fly off store shelves in South Korea.Just a few short of a full 159-sticker collection, 29-year-old Mr. Jeong has gone to more than 10 convenience stores and supermarkets a day, often leaving empty-handed. He has shelled out hundreds of dollars. He has learned the evening restock times throughout his neighborhood to know when fresh drop-offs occur.“As kids we really couldn’t afford enough pastries to have a shot at getting a full sticker set,” said Mr. Jeong, a clothing store owner who lives in the central South Korean city of Chungju. “I will continue on until I finish.”More than two decades ago, the Pokémon sticker-and-treat duo caught on with a generation of South Korean children, before the craze passed after a few years and the products were discontinued. Now the goodies are back just in time for the country’s broader retro boom, fed by tech-savvy adults nostalgic for simpler times.South Koreans are going to great lengths to live out the Pokémon tagline of “Gotta catch ’em all,” with some collecting the stickers in display booklets. Pokémon, originally a Japanese game for the Nintendo Game Boy that features hundreds of monster characters, has expanded into globally popular animated series, toys and videogames, including the recent hit Pokémon Go for smartphones. ▲ Pokémon stickers included in the pastries ▲ Customers waited in line to purchase Pokémon pastries.

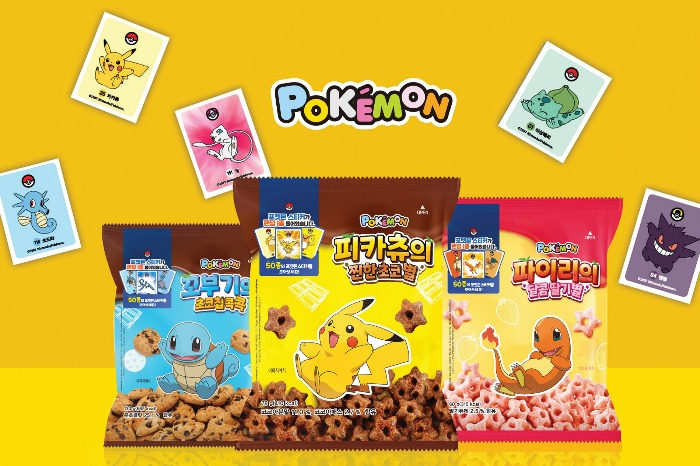

Retailers have posted signs on their entrances that read, “We have no Pokémon bread,” while some store owners stand accused of bundling the in-demand pastries with unpopular items. Hunters camp outside supermarkets early in the morning. The rarest of stickers, such as that of the legendary characters Mew and Mewtwo, fetch $40 online. Full collections command more than $700, the listings show. Actual children also try to find the stickers, but adults are using their greater resources for the hunt.Ko Hyo-jin shrieked when she ripped open a package of “Diglett Strawberry Custard Bread” recently and discovered inside a sticker of Mewtwo—a two-legged monster shown extending its paw. She immediately dialed up her husband. “It felt like winning the lottery,” said the 39-year-old homemaker in the Seoul suburbs.For months, Ms. Ko had been cooped up indoors studying for a veterinary-technician license exam. She planned to blow off post-exam steam by binge-watching Netflix shows. Instead, she went on a Pokémon hunt that forced her outdoors, walking around to different stores near her home. “Collecting the stickers felt almost as if I were actually catching Pokémon monsters,” she said.Son Mi-sun, who owns and manages a 7-Eleven convenience store in Seoul, receives just a handful of Pokémon pastries daily at around 9 p.m.—sometimes just one. But most nights three to five customers are waiting as the delivery truck pulls in.“I don’t know why the quantity is so limited,” Ms. Son said. “It could be a marketing ploy orchestrated by the manufacturer.”Absolutely not, said the South Korean maker of the pastries, SPC Samlip Co. , which says its three factories are running 24 hours a day since the Pokémon treats were re-released several weeks ago. “There is simply too much demand,” said a spokesman for SPC Group, which makes a variety of brands and runs restaurant and bakery chains. Last week, SPC introduced four new types of Pokémon bread and said new variations are coming in the future.The Pokémon Co., which handles the brand’s licensing and merchandising, didn’t respond to requests for comment.The nostalgic chase has been embraced by young adults facing Korea’s stagnant economy, soaring real-estate prices and a tight labor market. Improving the economic prospects for the country’s youth was a key campaign issue in South Korea’s recent presidential election.The trend has also resurrected retired snack lines and boosted vinyl-record sales and sticker photo booths. Makers of soju—South Korea’s ubiquitous rice liquor—have swapped in decades-old labels and translucent bottles. One rebrand is simply named: “Jinro Is Back.”When the doors of a large supermarket in Seoul swung open at 10 a.m. on a recent weekend, a line of roughly 100 customers had already formed. They gawked at piles of “Charmander’s Hot Sauce Bread,” “Pikachu Moist Cheesecake” and other varieties.“Please note that only two items are allowed per person,” announced a supermarket employee. The shelves emptied in less than 15 minutes. “It’s been like this every day for more than a week or so,” the employee said.Moon Sung-won, a 29-year-old teacher from Chungju, has eaten about 30 of the Pokémon items so far, sampling each of the flavors. They taste OK for the low price but aren’t phenomenal, he said. “Team Rocket Choco Roll” and “Gastly Choco Bread,” plus the “Jigglypuff Fluffy Strawberry Bread,” could use more cream, he said. The “Squirtle Sweet Crunchy Bread” is shaped like a turtle’s shell—and might taste like one, too. “It’s too hard, stale,” said Mr. Moon, who has at one point waited up to two hours to get the items.Ms. Ko said she gave away most of the 200 pastries she bought, just keeping the stickers. “After eating dozens, it became hard to even look at the packaging,” Ms. Ko said.Kuk Il-hoon, a 32-year-old tech worker in Seoul, has chronicled his quest for Pokémon bread on Instagram. One recent weekend he visited 30 convenience stores and logged 13,000 steps. He struck out each time. Then, after looking up tips online, he shifted tactics to go to the larger supermarkets with more plentiful supply, where he finally found success.Mr. Kuk is determined to build the collection naturally, swearing off purchasing any stickers through online secondary markets.“Doing so would feel like cheating,” Mr. Kuk said. “I don’t want to taint my childhood memories.”by Jiyoung Sohnjiyoung.sohn@wsj.com

Most Read